Between the Arctic blast of cold air today (which brought temperatures down to under 10C in the daytime, even down here in Gyeongju, with morning low near freezing), and the presence of groups of out-of-control schoolchildren at all my venues, I had a very tough day. But I enjoyed every bit of it.

It was interesting to note that for many of the elementary school students I saw around, the cell phone was the main means of taking notes. After all, they text message all the time anyway, Korean texting on a 10-digit keypad is extremely fast and efficient, and it may even be faster than writing on a piece of paper.

I covered all major sights in Gyeongju, thanks to my aggressive, demanding schedule and my ability to drive around in my own car; if using mass transit or taxicabs, it will certainly take much longer. In any case, I will certainly miss Gyeongju.

I started at the National Museum, the premier depository of Silla-era art, located next to Anapji. I loved the fact that it, like all South Korean national museums, had free admissions until December 31st, to mark the 60th anniversary of South Korea's government. Nevertheless, an entry ticket must be requested and obtained first at the ticket office.

I started at the National Museum, the premier depository of Silla-era art, located next to Anapji. I loved the fact that it, like all South Korean national museums, had free admissions until December 31st, to mark the 60th anniversary of South Korea's government. Nevertheless, an entry ticket must be requested and obtained first at the ticket office.This is the museum's star attraction: the Divine Bell of King Seongdeok, or Emille Bell, cast in 771. This is the greatest bell in Korea, and the largest and heaviest in the world (365 cm tall, 18,908 kg).

The Emille Bell got its nickname due to the legend that because the bell didn't ring right, a baby was thrown into the molten metal, and as a result, the bell now makes the sound of a baby - "emileh" - crying for its mother. However, given Silla's Buddhist culture and its respect for sanctity of life, it's just that - a legend. To be sure, the metal was analyzed, and no phosphorus (the ingredient of human bones) was detected.

This bell is National Treasure No. 29.

Silla ran from 57 BCE, when Park Hyeokgeose founded the kingdom as Seorabeol, until 935 CE, when it surrendered to the new kingdom of Goryeo, stretching nearly a millennium. The name Silla was adopted in 307 CE, and it unified Korea in 668.

To escape the bitter cold outside, I ducked into the archaeological collections room. This is a goblin-faced roof tile.

To escape the bitter cold outside, I ducked into the archaeological collections room. This is a goblin-faced roof tile. This is a prehistorical petroglyph, found in the once-sleepy fishing village of Ulsan, 30 miles to the south (and now a metropolis and an industrial powerhouse, with the largest automotive plant and shipyard in the world - both owned by Hyundai - and a per capita income of USD $40,000). The petroglyph depicts three turtles on the left, a whale carrying her baby on the right, and a male shaman on top praying for good whaling. The male shaman is notable for his huge penis and tail.

This is a prehistorical petroglyph, found in the once-sleepy fishing village of Ulsan, 30 miles to the south (and now a metropolis and an industrial powerhouse, with the largest automotive plant and shipyard in the world - both owned by Hyundai - and a per capita income of USD $40,000). The petroglyph depicts three turtles on the left, a whale carrying her baby on the right, and a male shaman on top praying for good whaling. The male shaman is notable for his huge penis and tail.This is National Treasure No. 285.

Silla's metallurgy was quite advanced. Here are some iron armor plates.

Silla's metallurgy was quite advanced. Here are some iron armor plates. Here is a glass and jade necklace. Glass was introduced to Silla from the Middle East by way of the Silk Road.

Here is a glass and jade necklace. Glass was introduced to Silla from the Middle East by way of the Silk Road. Silver and gold kitchenware.

Silver and gold kitchenware. Gold earrings. Silla's goldsmiths were among the finest in the world.

Gold earrings. Silla's goldsmiths were among the finest in the world. Gold belt and crown. National Treasures No. 87 and 88.

Gold belt and crown. National Treasures No. 87 and 88. Silla's pottery.

Silla's pottery. Another example of Silla pottery. The inside of the lid shows some cursive writing using Chinese characters. Silla had writing from early on, and as it unified Korea and blossomed its Buddhist culture, writing rose to new heights.

Another example of Silla pottery. The inside of the lid shows some cursive writing using Chinese characters. Silla had writing from early on, and as it unified Korea and blossomed its Buddhist culture, writing rose to new heights. Some of the twelve symbols of the Chinese zodiac. These symbols are, from left to right, ox, tiger, hare, snake, horse, sheep, and dog.

Some of the twelve symbols of the Chinese zodiac. These symbols are, from left to right, ox, tiger, hare, snake, horse, sheep, and dog.Silla learned the Chinese zodiac in the 7th Century, and used it extensively. It was the only civilization in the world to apply the Chinese zodiac to Buddhist contexts.

As Buddhism spread in Silla, people were cremated after death. This is a rather elaborate urn.

As Buddhism spread in Silla, people were cremated after death. This is a rather elaborate urn. These clay figurines are a rare way to look into the psychology and culture of everyday Silla people. Remember that records are quite scarce from this period, as paper had not been invented yet.

These clay figurines are a rare way to look into the psychology and culture of everyday Silla people. Remember that records are quite scarce from this period, as paper had not been invented yet. I was very disappointed when I found Dabotap at Bulguksa surrounded by scaffolding for archaeological work and renovation. Now, I get to see a full-size replica. This is one very gorgeous, intricate pagoda. Unlike the original, whose spire is quite worn out, this one has its spire intact.

I was very disappointed when I found Dabotap at Bulguksa surrounded by scaffolding for archaeological work and renovation. Now, I get to see a full-size replica. This is one very gorgeous, intricate pagoda. Unlike the original, whose spire is quite worn out, this one has its spire intact. And this replica does have all four lions, though they guard the corners rather than the staircases.

And this replica does have all four lions, though they guard the corners rather than the staircases.The 10-won coin has an image of Dabotap, complete with its lone lion. An urban legend popular among Christians used to say that the lion, only a millimeter or so tall on the coin, had been morphed into a Buddha, so that every South Korean would have a Buddha in his/her possession at all times, and that would ensure a Buddhist (such as General Roh Tae-woo) would be elected President rather than a Christian (such as Kim Young-sam or Kim Dae-jung).

Dabotap and Seokgatap full-size replicas stand here together. They are a very gorgeous sight.

Dabotap and Seokgatap full-size replicas stand here together. They are a very gorgeous sight. The museum has a special hall for Anapji excavation finds. This is a boat made from three logs. It's a transitional piece from a one-log canoe to a fully framed boat made of many planks of wood.

The museum has a special hall for Anapji excavation finds. This is a boat made from three logs. It's a transitional piece from a one-log canoe to a fully framed boat made of many planks of wood. This is a very exotic-looking roof crest. It's certainly more exotic in my eyes than the ones used by later Korean kingdoms.

This is a very exotic-looking roof crest. It's certainly more exotic in my eyes than the ones used by later Korean kingdoms. This model shows the best guess as to what Anapji would've looked like in its heyday.

This model shows the best guess as to what Anapji would've looked like in its heyday. Silla was a close ally of Tang China. Lots of Tang pottery were found at Anapji.

Silla was a close ally of Tang China. Lots of Tang pottery were found at Anapji.Tang China helped Silla defeat its Korean rivals and unify Korea, though Tang then betrayed Silla in an attempt to capture all of Korea for China. Although Silla kept its identity and sovereignty, it ended up paying tributes to the Chinese emperor - a practice Korea continued to follow, with a strong Confucian fervor during the Joseon era, until 1897.

Stone railing found at Anapji, reconstructed using a mix of original and replacement stone pieces.

Stone railing found at Anapji, reconstructed using a mix of original and replacement stone pieces. A bronze doorknob.

A bronze doorknob. "Phoenix," to me, usually connotes the Arizona city. And I am also reminded that the Secret Service refers to John McCain as Phoenix as well. But really, the phoenix is an immortal bird, as shown here.

"Phoenix," to me, usually connotes the Arizona city. And I am also reminded that the Secret Service refers to John McCain as Phoenix as well. But really, the phoenix is an immortal bird, as shown here. Top: wooden figurines.

Top: wooden figurines.Bottom: two wooden phallic symbols.

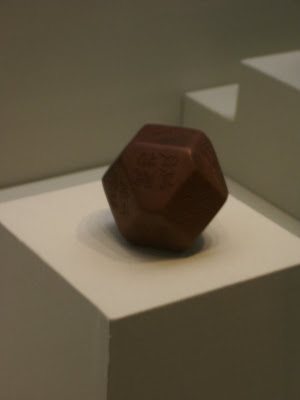

This weird-looking die, a replica, has some cryptic instructions written on each side in Chinese characters. It is believed that it was used in a social drinking game. Some of the instructions are as follows (best archaeologist guesses):

This weird-looking die, a replica, has some cryptic instructions written on each side in Chinese characters. It is believed that it was used in a social drinking game. Some of the instructions are as follows (best archaeologist guesses):- Drink three glasses of liquor in one shot.

- Never abandon your ugly partner.

- Sing a song. The song's title is also specified.

- Recite a poem.

- Let others strike your nose. Ouch!

- Drink up with arms bent.

- Dance silently.

- Remain still as others tickle your face.

- Remain calm as others assault you.

- Sing and drink.

- Ask anybody to sing a song of your choice.

- Drink, then laugh out loud.

Anapji was a royal garden with lots of animals, domesticated and wild. Here is a dog skull found there.

Anapji was a royal garden with lots of animals, domesticated and wild. Here is a dog skull found there. I'm back outside, looking west. This scene could only be Gyeongju. Rice paddies in front, a village in the distance at the foothills, and some tombs above the village.

I'm back outside, looking west. This scene could only be Gyeongju. Rice paddies in front, a village in the distance at the foothills, and some tombs above the village. Some construction materials excavated from Gyeongju's numerous ruins.

Some construction materials excavated from Gyeongju's numerous ruins.Unfortunately, most of Gyeongju's storied sites are now in ruins, due to frequent warfare in Korea over the centuries. But what does remain is still extremely impressive.

This is another typical Silla three-story Buddhist pagoda. It was moved here from the site of a nearby Buddhist temple by the name of Goseonsa, and is dated to before 686. Goseonsa's site is now underwater, as a dam was built nearby in 1975 as part of South Korea's massive dam-building and irrigation drive. This is another National Treasure - No. 38.

This is another typical Silla three-story Buddhist pagoda. It was moved here from the site of a nearby Buddhist temple by the name of Goseonsa, and is dated to before 686. Goseonsa's site is now underwater, as a dam was built nearby in 1975 as part of South Korea's massive dam-building and irrigation drive. This is another National Treasure - No. 38.Korean Buddhist pagodas tend to be stone, due to durability and low cost. Chinese ones tend to be brick, while Japanese ones tend to be wood. The first Korean pagodas were wood as well, but lightning and warfare tended to burn them down.

The Korean term for stone pagoda is seoktap (石塔), which is short for seokjotappa (石造塔婆). "Tappa" is the Korean translation of the Chinese characters (塔婆) that spell out the Indian word "stupa."

Another Goseonsa relic, among many here, is this headless turtle, the base of a now-gone tombstone.

Another Goseonsa relic, among many here, is this headless turtle, the base of a now-gone tombstone. A Buddhist stone lantern, which lights the world with the wisdom of the Buddha. The first Korean stone lantern was built at Mireuksa (Maitreya Temple) in Iksan, in the southwest; it will certainly be part of my next South Korean road trip. This particular example was erected in the 8th or 9th Century within Gyeongju.

A Buddhist stone lantern, which lights the world with the wisdom of the Buddha. The first Korean stone lantern was built at Mireuksa (Maitreya Temple) in Iksan, in the southwest; it will certainly be part of my next South Korean road trip. This particular example was erected in the 8th or 9th Century within Gyeongju. I've now entered another hall, with an artistic focus. There are two stone Buddha heads, both depicting Sakyamuni.

I've now entered another hall, with an artistic focus. There are two stone Buddha heads, both depicting Sakyamuni. Koreans didn't make too many bronze statues, due to the high costs involved, but here is a bronze Medicine Buddha. Dating from the late 8th Century, it is another National Treasure - No. 28.

Koreans didn't make too many bronze statues, due to the high costs involved, but here is a bronze Medicine Buddha. Dating from the late 8th Century, it is another National Treasure - No. 28. Here's the fabled eleven-faced Kwan Yin. The other ten faces are on her crown.

Here's the fabled eleven-faced Kwan Yin. The other ten faces are on her crown. Two examples of Pensive Bodhisattva. While most Buddhist statues tend to look directly ahead at the observer, Pensive Bodhisattvas look down, emphasizing the reflective nature of Buddhist meditation.

Two examples of Pensive Bodhisattva. While most Buddhist statues tend to look directly ahead at the observer, Pensive Bodhisattvas look down, emphasizing the reflective nature of Buddhist meditation.India, China, and Japan are also known for their own Pensive Bodhisattvas.

Here are two bodhisattvas. The left is a generic one while the right is a Kwan Yin.

Here are two bodhisattvas. The left is a generic one while the right is a Kwan Yin.Nearby, there are other statues I couldn't get pictures of in decent quality. They include the Newborn Buddha, which depicts baby Sakyamuni right after his birth from the side of his mother, clad in only a miniskirt. There also are a Vairocana or two.

Here's a lion climbing a pole.

Here's a lion climbing a pole. Quite a sight - miniature pagodas, only 2 inches tall.

Quite a sight - miniature pagodas, only 2 inches tall. This is a silver ritual bottle. It is from the Goryeo era, which followed Silla, and was found in Daegu, an hour's drive to the west.

This is a silver ritual bottle. It is from the Goryeo era, which followed Silla, and was found in Daegu, an hour's drive to the west. This miniature bell shows the features of a Korean bell very well. Instead of a double-headed dragon at the top hinge as is the case with Chinese bells, this bell has a single-headed dragon. There also are acoustic chambers, which are not found in Chinese and Japanese bells. In fact, Koreans bells are different enough that while Chinese and Japanese bells use the character 鐘, a combination of gold (金) and child (童), Korean bells use the character 鍾, replacing the child with the heavy (重).

This miniature bell shows the features of a Korean bell very well. Instead of a double-headed dragon at the top hinge as is the case with Chinese bells, this bell has a single-headed dragon. There also are acoustic chambers, which are not found in Chinese and Japanese bells. In fact, Koreans bells are different enough that while Chinese and Japanese bells use the character 鐘, a combination of gold (金) and child (童), Korean bells use the character 鍾, replacing the child with the heavy (重). This human-faced roof end tile was made in the 7th Century, and discovered at Yeongmyosa Site in Gyeongju. It is a very common motif on Gyeongju souvenirs.

This human-faced roof end tile was made in the 7th Century, and discovered at Yeongmyosa Site in Gyeongju. It is a very common motif on Gyeongju souvenirs. A marvelous sight in downtown Gyeongju that no longer exists today. This is a model of Hwangryongsa (Temple of Yellow Dragon). Originally, it was to be a palace, but when a yellow dragon showed up at the construction site in 553, the plans changed to a temple. The first phase was finished in 569, and the trademark 9-story wooden tower was completed in 646. The temple was destroyed by fire in 1238 during a Mongol invasion, and never rebuilt; nevertheless, tens of thousands of artifacts have been discovered at the site over the years.

A marvelous sight in downtown Gyeongju that no longer exists today. This is a model of Hwangryongsa (Temple of Yellow Dragon). Originally, it was to be a palace, but when a yellow dragon showed up at the construction site in 553, the plans changed to a temple. The first phase was finished in 569, and the trademark 9-story wooden tower was completed in 646. The temple was destroyed by fire in 1238 during a Mongol invasion, and never rebuilt; nevertheless, tens of thousands of artifacts have been discovered at the site over the years. Here is a Pensive Bodhisattva that once stood on a Gyeongju mountain. He has lost his arms and head, but is still impressive.

Here is a Pensive Bodhisattva that once stood on a Gyeongju mountain. He has lost his arms and head, but is still impressive. Here is another stone Kwan Yin. The head had been in the museum's collection for decades, but the body was half-buried on some mountainside. Studies in 1997 determined that the body and the head belonged to the same statue, and they were reunited and erected here.

Here is another stone Kwan Yin. The head had been in the museum's collection for decades, but the body was half-buried on some mountainside. Studies in 1997 determined that the body and the head belonged to the same statue, and they were reunited and erected here.I finished by visiting a special exhibit on trade and cultural exchanges between Silla and the Middle East. While most scholars tend to concentrate on Silla's ties to its Korean rivals, as well as to Chinese and Japanese states, Silla did have plenty of ties outside the region as well. Glassmaking came to Silla via the Silk Road, and some Silla motifs incorporate Persian and other design elements. Toward the latter centuries, there is even documented evidence of a Muslim community in Silla, as well as Silla statues depicting Middle Easterners. While I was unable to take photos due to regulations, I nevertheless got to see some great Middle Eastern art, especially those from nations hostile to the US, including Iran and Syria. It's difficult for me to see those nations' artwork back home, and if war breaks out between the US and Iran and countless pieces of art get destroyed (I fear the repeat of what happened in 2003 in Baghdad, as the museums got looted while only the Oil Ministry was protected), I may never get a chance to see them again.

I then started driving south, to a series of peaks collectively known as Namsan.

Poseokjeong, seen here, is a well and a 6-meter-long viaduct. This is part of a royal garden; the rest of the garden no longer exists. It was nice to come in here for 500 won, though I hated paying another 2,000 won just for the privilege of parking. I wouldn't have parked here, had I known that the mountain trails I was looking for were farther south.

Poseokjeong, seen here, is a well and a 6-meter-long viaduct. This is part of a royal garden; the rest of the garden no longer exists. It was nice to come in here for 500 won, though I hated paying another 2,000 won just for the privilege of parking. I wouldn't have parked here, had I known that the mountain trails I was looking for were farther south. Next to Poseokjeong is this traditional village, complete with a small neighborhood Buddhist temple.

Next to Poseokjeong is this traditional village, complete with a small neighborhood Buddhist temple.I drove a bit farther south, paid another 2,000 won to park, then took a trail up the western slopes of Namsan. Namsan has all sorts of Buddhist relics scattered over, and I was able to see a few of them. I took the Samneung (Three Tombs) Valley Trail.

This is a seated stone Buddha, located in the Samneung Valley. It was erected here after being found by Dongguk University students 30 meters away in 1964. It has very striking details, despite missing its head and hands.

This is a seated stone Buddha, located in the Samneung Valley. It was erected here after being found by Dongguk University students 30 meters away in 1964. It has very striking details, despite missing its head and hands.As shown by the altar below, all Buddhist relics in the mountain are active worship sites. The faithful light candles, make offerings, and pray.

40 meters away from the Buddha, on top of a very steep set of stairs, is this Kwan Yin, carved into a boulder. So nice to keep coming across my transgender matron saint. I really want to take her spirit into my everyday life in America, and will do everything to make that happen.

40 meters away from the Buddha, on top of a very steep set of stairs, is this Kwan Yin, carved into a boulder. So nice to keep coming across my transgender matron saint. I really want to take her spirit into my everyday life in America, and will do everything to make that happen. Walking farther up the mountain, I was able to come across a well-known set of six Buddhist figurines, carved into two boulders. This is the first set, with a Buddha standing on a lotus flower, flanked by two kneeling bodhisattvas.

Walking farther up the mountain, I was able to come across a well-known set of six Buddhist figurines, carved into two boulders. This is the first set, with a Buddha standing on a lotus flower, flanked by two kneeling bodhisattvas. Slightly behind and to the right, three more figurines are present, though quite worn out. The Buddha is seated, while the bodhisattvas are standing. Above and to the right, the caption board says there are traces that there used to be a monastery here as well.

Slightly behind and to the right, three more figurines are present, though quite worn out. The Buddha is seated, while the bodhisattvas are standing. Above and to the right, the caption board says there are traces that there used to be a monastery here as well.I decided to cap my climb here, and return to my car.

Namsan's trails are well-maintained for the most part, and clearly signposted, though some unofficial trails can make hiking a bit of an adventure. It's pretty difficult to get lost in any case.

Namsan's trails are well-maintained for the most part, and clearly signposted, though some unofficial trails can make hiking a bit of an adventure. It's pretty difficult to get lost in any case.The signs are in Korean, Chinese, and English, and also show distances to each attraction in meters. The English names are no more than romanized Korean names, however. It will help immensely to remember what each suffix means; "sa" (寺) is a temple, "am" (庵) is a grotto, and "reung" or "neung" (陵) is a tomb.

After rounding Namsan and refueling my car, I returned east to the Bomun Lake Resort district, where a cultural exposition park is located, within walking distance of my hotel. Admission is 5,000 won (not including the fossil museum, which costs slightly extra), and parking is free.

After rounding Namsan and refueling my car, I returned east to the Bomun Lake Resort district, where a cultural exposition park is located, within walking distance of my hotel. Admission is 5,000 won (not including the fossil museum, which costs slightly extra), and parking is free.Its star attraction is the Gyeongju Tower, which has a cutout in the shape of Hwangryongsa's 9-story pagoda. It has a museum 65 meters above ground, and an observatory 82 meters above ground.

I'm at the museum. I am looking at Gyeongju at its peak, from the northwest. In the foreground is Tumuli Park. The middle right is Cheomseongdae, with Banwolseong above and to the right of it. Anapji is just beyond Banwolseong, while Hwangryongsa dominates the skyline in the far distance.

I'm at the museum. I am looking at Gyeongju at its peak, from the northwest. In the foreground is Tumuli Park. The middle right is Cheomseongdae, with Banwolseong above and to the right of it. Anapji is just beyond Banwolseong, while Hwangryongsa dominates the skyline in the far distance. Here are some Palestinian glass vessels, brought to Silla via Silk Road.

Here are some Palestinian glass vessels, brought to Silla via Silk Road. This replica of a frieze found in Samarkand, Kazakhstan, shows two Silla envoys (far right) visiting Samarkand. The envoys give away their nationality through their outfits, and this is proof that Silla's trade and cultural activities took place along the Silk Road, well beyond the classic China-Korea-Japan boundary.

This replica of a frieze found in Samarkand, Kazakhstan, shows two Silla envoys (far right) visiting Samarkand. The envoys give away their nationality through their outfits, and this is proof that Silla's trade and cultural activities took place along the Silk Road, well beyond the classic China-Korea-Japan boundary. There is also an opened-up model of Seokguram. This is the eleven-faced Kwan Yin at the very rear.

There is also an opened-up model of Seokguram. This is the eleven-faced Kwan Yin at the very rear. I am looking at Bomun Lake and its resort facilities. The middle left has an amusement park. Farther away, a fountain and some swan-shaped pleasure boats can be seen. The pink building in the center right is the Hilton.

I am looking at Bomun Lake and its resort facilities. The middle left has an amusement park. Farther away, a fountain and some swan-shaped pleasure boats can be seen. The pink building in the center right is the Hilton.There are other attractions here, including 3-D movies with traditional Silla motifs, a display of Korean-designed characters (which have largely supplanted Japan's Hello Kitty, and one of them, Mashimaro, is commonly seen even in the US), and even a hall of 52 reproduced Western paintings displayed under license from the French Cultural Board (I certainly loved seeing Mona Lisa, Rembrandt's Nightwatch, and a whole slew of other paintings that I had seen in person in my European trips). Schoolchildren on field trips really annoyed me, however, especially at the movies.

I drove about 20 miles east, to the Sea of Japan coast. Here is the underwater tomb of King Munmu, who ruled from 661 to 681, and unified Korea for the first time. There is a pond in the middle of those rocks, and in it, a granite coffin, 3.6m x 2.9m x 0.9m, sits, containing the cremated ashes of Munmu. Munmu asked to be buried here, so that he would continue to live on as a dragon, and protect Silla from future Japanese attacks. However, historical records differ on whether Munmu's ashes are actually interred inside the coffin, or whether they were scattered at sea instead.

I drove about 20 miles east, to the Sea of Japan coast. Here is the underwater tomb of King Munmu, who ruled from 661 to 681, and unified Korea for the first time. There is a pond in the middle of those rocks, and in it, a granite coffin, 3.6m x 2.9m x 0.9m, sits, containing the cremated ashes of Munmu. Munmu asked to be buried here, so that he would continue to live on as a dragon, and protect Silla from future Japanese attacks. However, historical records differ on whether Munmu's ashes are actually interred inside the coffin, or whether they were scattered at sea instead.This is Historical Site No. 158. Admission is free, as this is a public beach. However, parking does cost 1,000 won or 2,000 won, depending on time of day. I came around sunset, so I paid the night rate of 1,000 won.

Some squids are being dried on these lines, on the very beach across from the Munmu tomb. I loved the glimpse of a Korean seaside fishing town.

Some squids are being dried on these lines, on the very beach across from the Munmu tomb. I loved the glimpse of a Korean seaside fishing town. It's getting dark, and it's time to make the somewhat treacherous drive back to Gyeongju. A mile inland from the Munmu tomb, there is this temple site, right next to the road back to Gyeongju. It is Gameunsa; Munmu built this temple to seek Buddha's help in repelling Japanese invasions, and it was completed by his son, King Sinmun.

It's getting dark, and it's time to make the somewhat treacherous drive back to Gyeongju. A mile inland from the Munmu tomb, there is this temple site, right next to the road back to Gyeongju. It is Gameunsa; Munmu built this temple to seek Buddha's help in repelling Japanese invasions, and it was completed by his son, King Sinmun.Aside from building foundations, nothing remains here, except for a pair of twin 3-story stone pagodas, 13.4 meters tall. They are, again, National Treasures - No. 112. The pagodas' spires, long gone, have been replaced by modern metal spikes, designed to protect them from lightning strikes. The west pagoda (far) was dismantled, researched, and renovated in 1959-1960, while the east one (near) had the same done in 1996.

My drive back to Gyeongju took me through some rural villages, one of which boasted a restaurant serving dog meat soup (boshintang) - something extremely freakish and upsetting to me, but considered a delicacy by some. If that, in addition to all the art and history, doesn't tell me I'm in Korea, I don't know what does.

And with this, my Gyeongju sightseeing - two intense days of lots of driving and walking, and full of historical relics - is finished. This is one trip to surely remember for a long time. I will need to drive back to Seoul tomorrow morning, but I expect to stop at three Buddhist temples on the way, so the Buddhist theme lives on. And even after I arrive in Seoul, I will continue to drive around for several more days, and visit lots of places on day trips.

One last thing, however. The Koreans continue to always refer to Kwan Yin as "Avalokitesvara," her Indian male name, whenever referring to her in English. I'm not too happy. If people continued to refer to me by a male name, I certainly won't be happy!